A bit of BaTi0.9Zr0.1O3

Published:

In this post you will see a bit about the Barium Titanate (BaTiO3) with the inclusion of zirconium, i.e., the BaTi0.9Zr0.1O3 material. I start with the motivation behind this work and its objectives. Then, I describe the methodology to produce the powders and the pellets, and finalize with the electric characterization of the materials produced.

This post refers to my first Scientific Initiation, in materials production (more specifically pellets of BaTi0.9Zr0.1O3), that I have made in 2012. This work was done under advisor of Professor Antonio Carlos Hernandes and and student co-orientation of the PhD Thiago Martins Amaral.

The motivation behind the work

Barium titanate (BaTiO$_{3}$) is a multifunctional material with wide technological application (it is used in capacitors, eletromechanical transducers and even in nonlinear optics) and arouses great scientific interest by being a ferroeletric ceramic and due to its different physical properties (for instance, ferroelectricity and piezoelectricity).

Its structure is of the perovskite type, where each unit cell is composed of an octahedron formed by oxygen in the centers of the faces, barium atoms at the vertices of the polyhedron and a titanium atom in the center of the octahedron, if it is in the cubic phase.

Figure 1: Structure of the barium titanate on its cubic phase.

In addition to the cubic phase for temperatures above $120^{\circ}C$, BaTiO3 has three more phases: between $120^{\circ}C$ and $5^{\circ}C$ there is the tetragonal phase, between $0^{\circ}C$ and $-70^{\circ}C$ there is the orthorhombic phase and below $-70^{\circ}C$ the rhombohedral phase [1].

Figure 2: Structure phases of the barium titanate according to temperature.

One of the main properties of this material is ferroelectricity, which consists of the presence of an electrical polarization that can be reversed by the action of an external electric field. The origin of ferroelectricity is in the displacement of titanium in relation to the center of the oxygen octahedron in the tetragonal, orthorhombic and rhombohedral phases, however, in the cubic phase the displacement of Ti does not exist and it is a paraelectric phase.

The ease with which these dipoles can be reoriented gives rise to a very high electrical permittivity ($> 10,000$), making this material an interesting dielectric medium for capacitors. This allows for large capacitance even in very small devices, which is of fundamental importance for the miniaturization of electronic equipment. However, this material has its maximum permittivity during the ferroelectric/paraelectric transition at $120^{\circ} C$ and it would be interesting to extend this maximum permittivity to temperatures closer to the environment. This can be achieved by adding Zr instead of Ti, as it is known that this substitution decreases the temperature of the phase transition, opening the possibility for the creation of BaTi$_{(1-x)}$Zr$_x$O$_3$ composites with different values of $x$. These composites would have a maximum permittivity around the transition temperatures of each component of the composite [2].

The objective of the work

The objective of the work is the production of pellets of BaTi0.9Zr0.1O3 and characterization of the material obtained in its subsequent use in the manufacture of composites and studies of its electrical properties, aiming at extending the maximum permittivity to regions of temperatures lower than $120^{\circ}C$.

Methodology, procedures and results

The powder

The production of the material was made from the stoichiometric calculation for $5 g$ of BaTi0.90Zr0.10O3, material composed of BaCO3, TiO2 and ZrO2 in which the powder was homogenized in a zirconia ball mill by $24$ hours in isopropyl alcohol. A first heat treatment (calcination) was carried out at $1200^{\circ}C$ for $2$ hours and a second grind for $72$ hours, just like the previous one, in order to reduce the size of the particles.

The structural characterization of the material was made by X-ray diffraction using the powder method and scanning electron microscopy. To obtain the particle size distribution, a visual count was made with the measurement of their respective sizes in the ImageJ software (at that time I didn’t realize the importance of this software. To see an interesting explanation of its functionalities and general importance, I certainly recommend the Nature’s article).

Results

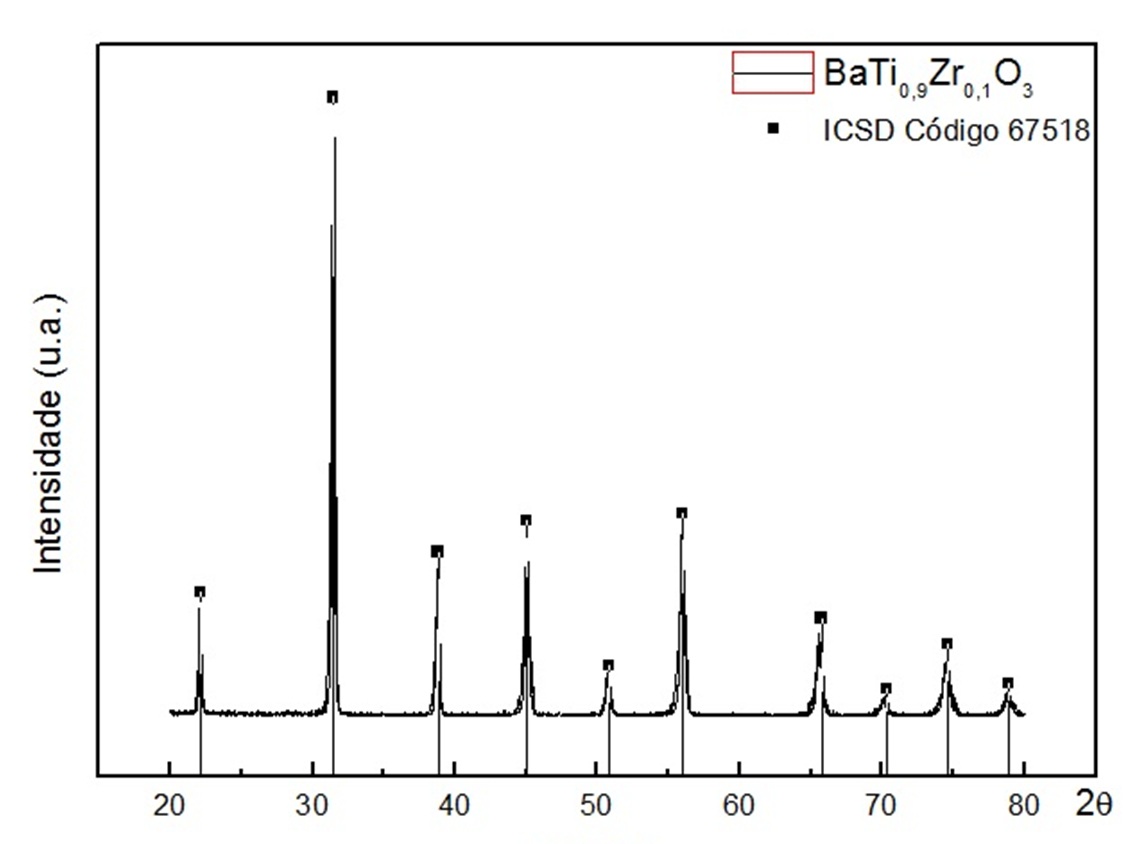

The diffractogram of the material revealed the formation of the desired phase, i.e., that the resulting material was exactly the compound BaTi0.90Zr0.10O3 [3].

Figure 3: Diffractogram of the material after thermal treatment.

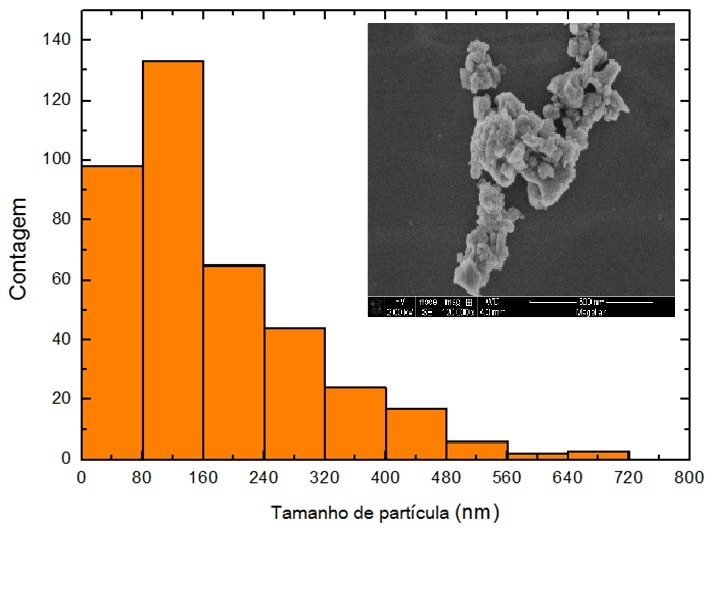

Then, the micrographs and the histogram reveal particles with an average size of $170 nm$, different shapes and wide particle distribution (standard deviation of $130 nm$).

Figure 4: Micrograph (obtained by scanning electron microscopy) and the histogram for the particle’s size.

Pastillization and sinterization

The powder was pelletized and sintered, with two constant levels of temperature. Then, sintered ceramic body was obtained and followed with application of its platinum electrodes.

Figure 5: A picture of the pellets on platinum support.

Permittivity

The electric characterization was made using, specifically, the permittivity. The permittivity is a measure of the electric polarizability of a dielectric, and it is represented by $\epsilon$. This quantity was measured according to its answer to temperature.

.jpg)

Figure 6: Plots for electric permittivity $\epsilon$ of the pellets versus the temperature ($T$).

Expected results were obtained with some deviations due to possible contamination of the samples during milling in a ball mill, and the permittivity was very high (peak in $T \simeq 50^{\circ}C$ instead of $T \simeq 90^{\circ}C$) but with temperatures closer than the ambient for the doping performed.

References

[1] A.S. Bhalla, R. Guo and R. Roy: The perovskite structure - a review of its role in ceramic science and technology. Mat Res Innovat (2000) 4:3-26.

[2] B. Jaffe, W. R. Cook and H. Jaffe: Piezoelectric ceramics. Academic Press Inc. 1971.

[3] R. H. Buttner, E. N. Maslen, Acta Crystallographica B (39, 1983-) (1992) 48 p 764.